The history of cyclones goes back to 1891 when E. Bretney obtained the first patent (Bretney 1891). The Bretney cyclone was designed with a closed apex for intermittent discharge and was the forerunner to present-day desanders that are used for separating sand from water in pressurized water systems. The Bretney cyclone had a roof entry feed inlet that canted down into the main cyclone body. This first cyclone was a crude, unlined, mild steel cyclone, but it paved the way for bigger and better things to come.

Between 1891 and 1939, a number of patents were granted on cyclones, but the record shows very few commercial installations. One of the earliest references to a commercial installation during this time was a cyclone 1.6 m in diameter that was installed in a U. S. phosphate plant in 1914. Most of the patents granted during this early period covered the use of cyclones for cleaning paper stock. The early designs were typically crude and centered on the use of smaller-diameter cyclones handling relatively low flow rates. Some commercial installations of pulp and paper cyclones started to appear toward the end of the 1930s. Most of the work on these cyclones was being carried out in Europe. Interestingly, one of the first references to a cyclone with a siphon on the overflow and an elutriation of water at the bottom was recorded in 1929 in an English patent.

|

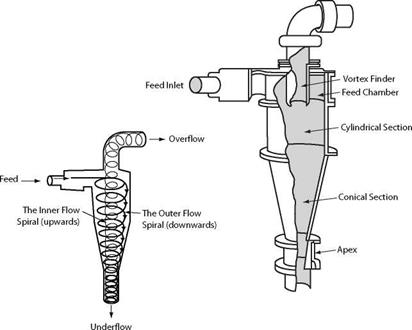

FIGURE 9.3 Hydrocyclone, showing the main components and principal flows (Napier-Munn et al. 1996; reprinted by permission from University of Queensland) |

In 1939, Dutch State Mines (DSM) started investigating the use of cyclones for the cleaning of coal. The first use of cyclones by DSM was to dewater the sand used to make up suspensions for heavy-medium separators. Around the same time, the Powell Duffryn Company in the United Kingdom was looking at using cyclones for dewatering coal ahead of screens, and it obtained a patent for a cyclone in which the apex section could be replaced to overcome abrasion.

In 1943, the first work on the use of conventional cyclones for liquid-liquid separations was undertaken at the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission, where scientists tried without success to use the centrifugal forces in the spiraling flow in cyclones to separate isobutanol and water (Tepe and Woods 1943).

The most prolific period for the development of the cyclone occurred from 1939 to 1948, when M. G. Driessen of DSM led the effort to develop the use of cyclones in coal preparation. The main applications investigated during that time were the dewatering of the sand suspension and the actual cleaning of coal from sand using the sand suspension. According to legend, the cyclone’s use for the cleaning of coal was due to a perceptive observer. Apparently, a cyclone that had been used by DSM staff for cleaning sand used in a coal concentration cone was dismantled for maintenance and it was noticed that the overflow pipe contained very clean fine coal. DSM engineers realized that two processes were involved:

■ A dewatering process in which the sand was concentrated in the outer spiral and left the cyclone through the apex while most of the water left through the vortex finder

■ A concentration process in which the centrifugal force enhanced the efficiency of the sand suspension as a dense-medium separator and caused the coal particles that contaminated the sand to move from the outer to the inner flow in the cyclone and enter the overflow

This observation about the effect of centrifugal force on gravity concentration led to the introduction of cyclone-based dense-medium equipment that changed the efficiency and economics of the beneficiation of coal, iron ore, and some sulfide ores, and to DSM developing a large business in dense-medium cyclones.

Driessen obtained many patents and published numerous papers, which fueled a worldwide interest in the commercialization of cyclones (Driessen 1948). Many people started using cyclones for clarifying water, removing solids from drilling mud, and for mineral concentration. In 1944, the Humphrey Investment Company, using Driessen’s published works, developed a Humphrey centrifuge—the first large-diameter commercial cyclone with a vortex finder, used to dewater mineral slurries ahead of the Humphrey spiral. Ironically, the original DSM cyclones did not have vortex finders, and it was not until 1948 that the commercial DSM cyclones incorporated these. The DSM patents were commercialized by Stamicarbon N. V., which licensed the technology to companies such as the Dorr Company (which later became the Dorr Oliver Company) for minerals and Heyl Patterson for coal.

The Dorr Company started marketing the Dorrclone in 1948. Stamicarbon continued research on the cyclone and in 1948 filed for the first known patent on the use of conventional cyclones for separating liquids and also for a patent on the use of an adjustable elastomer apex. The year 1948 saw tremendous activity with the cyclone around the world:

■ The Fuel Research Institute of South Africa started working with cyclones for coal washing in South Africa.

■ F. T. Doughty published one of the earliest technical papers on cyclones for mining in Mine & Quarry Engineering entitled “The Cyclone—Its Use for Mineral Concentration” (Doughty 1948).

■ One of the earliest reported uses of cyclones in the U. S. mining industry was small-diameter cyclones used at Chino Mines Division, Kennecott Copper, Hurley, New Mexico.

As the awareness of cyclones started to rise, other manufacturing companies besides the Dorr Company started looking at the cyclone as a viable product. In 1948, American Cyanamid started experimenting with a small-diameter DSM cyclone for heavy-medium coal separations and continued this work until 1950 when it turned over the designs and work to Kelly Krebs. Krebs had retired from American Cyanamid and started his own company, Equipment Engineers, in San Francisco, California. Krebs was acquainted with Bob Clarkson, who invented the Clarkson reagent feeder, and Krebs persuaded Cyana — mid to license and manufacture it.

In 1948, Driessen left Europe and came to the United States to work for Heyl Patterson. The coal industry continued to develop uses for cyclones, and most of the patents in the late 1940s and early 1950s were related to coal. In 1949, however, other industries began to recognize the potential of cyclones. The first reported tests of small-diameter cyclones for starch separations were conducted in Holland, resulting in the first commercial installation for gluten-starch separation. The Dorr Company, in cooperation with DSM, developed the first TM (tandem-multi) 10-mm cyclones for starch separations. Other reported uses of cyclones in 1949 included phosphate processing in Florida and iron ore processing in Minnesota and Russia (Wright 1949). It was around this time that the Dorr Company started to push the use of the cyclone in the mining industry.

D. A. Dahlstrom was an early investigator of cyclones, first at Northwestern University (Evanston, Illinois) in the late 1940s, and then at the Dorr Oliver Company in the early 1950s. He published some of the early modeling work on cyclones and was one of the first investigators to try and find out how a cyclone worked (Dahlstrom 1952; Emmett and Dahlstrom 1953). Dahlstrom’s work with the cyclone raised its visibility and led to significant research work at various universities around the world, including significant research by Kein and Ellefson at Northwestern on the use of cyclones for both liquid-solid separations and liquid-liquid separations. In 1952, Dahlstrom and the Dorr Company patented the first cyclone with a hydraulic water addition at the bottom to improve the efficiency of the cyclones.