With the success of primary autogenous milling and feed control at Union Corporation, primary autogenous mills became an accepted feature of Rand grinding practice. The autogenous mill circuits required about 25% more power than conventional circuits using pebble mills, but the smaller crushing circuit meant that there was lower capital investment and reduced maintenance cost.

Hadsel put his varied experience with the wet autogenous mill to good use when he built a dry primary autogenous mill in 1935. This large-diameter, short-length, air-swept mill initially rotated above the speed required to maintain a layer of centrifuged rock on the surface of the drum to reduce wear (the critical speed). In March 1936, a long mill (3.2 m x 1.6 m) was installed at the Harqua-Hala Gold Mines Company in Arizona, which eventually ground 90 tpd of -200 mm feed to 62% passing 75 pm. The mill eventually operated at 84% of the critical speed because of reduced capacity at higher speeds.

The new mill must have looked promising because, in 1937, Cominco, the large Canadian mining company, acquired the Canadian rights to the mill. It appointed David Weston, who had been mill superintendent at the New Golden Rose mine in northern Ontario, to manage the project. Cominco installed mills—one that was 3.9 m in diameter and 1.3 m long and another that was 2.9 in diameter and 2.0 m long—in its mines in Ontario and Northwest Territory, including the New Golden Rose mine, where it operated intermittently for 5 years, grinding 139 tpd to 66.5% passing 75 pm. Apparently most of the mills worked reasonably well, but in 1946 Cominco gave the rights to Weston, who set up Aerofall Mills Ltd. in Toronto. He made many improvements and by 1960 had sold about 20 mills. An Aerofall mill (6.0 m x 1.6 m) installed at the Benson iron-ore mine in New York in 1954 became “the first commercial autogenous mill in the world to process iron ore” (Roe 2000).

This sale was a milestone in autogenous milling because it opened up the low-grade iron ore market. Dry-grinding Aerofall mills were used in the third major installation of primary autogenous grinding mills in the Quebec Labrador trough, which was the Iron Ore Company of Canada’s Carroll Lake plant. This installation and one for grinding asbestos ore were the high points and early successes of Aerofall mills. The patents granted to Weston for the dry-grinding Aerofall mills specifically covered mills with 6%

|

|

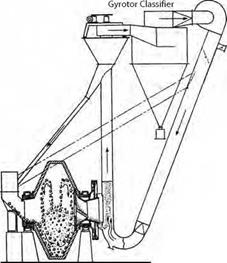

FIGURE 7.23 Dry mill and air separator (Hardinge 1955; reprinted by permission from Primedia)

of the mill volume containing steel balls and a mill speed of 82% of critical speed. The standard length for the mills designed by Aerofall Mills Ltd. was 1.9 m measured at the mill shell inside the liners. The Aerofall mill system was air swept and the air was heated sufficiently to dry any moisture in the mill feed. Some patents covered the installation of keying members at the throat of the mill at the feed and discharge ends to help lift the ore so that it would fall through the air stream. Figure 7.23 shows a dry mill and air separator.

In 1941, Hardinge supplied a dry mill (3.2 m x 1.6 m) to the Century Mining Corporation in Flin Flon, Manitoba. It had an electric ear for feed control and a 50-mm (2-in.) screen to separate the fine and coarse particles, allowing feed rates to the mill to be controlled. Although these features were important in the evolution of autogenous grinding and looked promising, they could not be thoroughly evaluated at the time because Century Mining Corp. closed during World War II and did not reopen.