In 1848, William Easby was granted a patent for a method of converting fine coal into solid lumps. In his application, Easby made only one claim: “The formation of small particles of any variety of coal into solid lumps by pressure.” In an equally brief description of the process, he mentions, “The utility and advantage of the discovery are that by this process an article of small value and almost worthless can be converted into a valuable article of fuel for steamers, forges, culinary and other purposes thus saving what is now lost.” In his few words, Easby patented the entire coal briquetting industry and also stated the rationale for its existence. Almost 50 years later, economic pressure joined forces with technological progress to give substance to Easby’s vision (K. R. Komarek Inc. 2002).

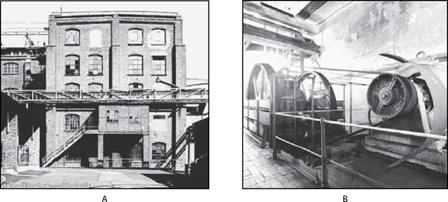

Easby added high-pressure machines to the armory of equipment that could be used to add value to solid particles, and, although they took a long time to make their mark, they were eventually proved to be very useful for both compacting and disintegrating solids. The first use of the high-pressure rolls was for compacting coal into briquettes, and by 1900 coal briquetting was a large industry in Europe and the United States. The many huge buildings housing the presses reflected the high volume of briquettes produced. Figure 6.17 shows a briquetting press in the Wachtberg lignite briquette plant in Frechen, Germany, which opened in 1901. Today’s presses work at 2,000 bar (29 psi).

High-pressure rolls were also built for duties other than forming lignite briquettes:

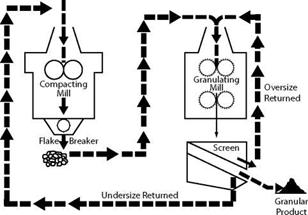

During the 1920s Allis-Chalmers started to build double-roll machines to compress fine solids into granules and flakes and with the development of hydraulic pistons the company was able to use the basic design of their granulators and flaking mills to manufacture a double-roll compactor. The fine material to be compacted is fed continuously into the nip of the rolls from above. This material is drawn between the rotating rolls where very high pressures are developed which would compact and agglutinate the feed so that a continuous sheet of product was ejected from the bottom of the rolls. The void content of the product may approach zero and the sheet thickness may vary from 0.25 to 0.020 inches. (Kurtz and Bar — duhn 1960)

Figure 6.18 is a flow sheet of the circuit in which the machine was used.

|

FIGURE 6.17 Wachtberg briquette plant in Frechen, Germany, which commenced operations in 1901 and in which high-pressure rolls were used to compact lignite into briquettes: (a) press house (b) machinery (Harald Finster 2002; reprinted by permission) |

|

Fine Material

|

FIGURE 6.18 Flow sheet of the circuit in which a compactor was used (Kurtz and Barduhn 1960)

During their passage through the gap between the rolls, the feed particles reoriented to reduce the void content. Next, the larger particles were crushed when the minimum void was approached, and this was followed by plastic deformation to minimize the volume.

The idea that a roll mill operating at very high pressure could be used as a crusher rather than a compactor was the basis of a mill-described in the next section—that was developed 70 years later in Germany.