Roller mills were used in China in the 2nd century for grinding the red mineral cinnabar to a vermillion pigment (Figure 6.1) and for grinding grains for cereal (Figure 6.2), and they are still used for these purposes today (Figure 6.3). In 1449, Pietro Speciale was credited with the development of a three-roller mill in Sicily; it was originally used for crushing sugar canes, and the rolls were made of wood mounted with vertical axes. In 1558 in Spain, Giovanni Turriano developed a roller mill with a conical roller with spiral grooves cut into it that rotated inside a grooved cone (Ramelli 1588; see Figure 6.4). It was powered by hand and apparently was small enough to fit inside the sleeve of a monk’s robe. Although it was said to be extremely productive, the concept was so far ahead of practice at the time that the mill was not widely used. In 1753, Issac Wilkinson in Italy obtained a patent for a mill with cast iron rolls (Research Association of the British Paint, Colour and Varnish Manufacturers 1953).

ARRASTRAS

In its simplest form the arrastra consists of a shallow circular bed, which is paved with closely set blocks of hard stone; upon this pavement two or more heavy drags of stone are slowly pulled round, thus crushing the ore under them. (Louis 1894)

(Arrastra) drag stones weigh from 80 to 2000 lb each. …they are placed so that the front edge of the stone may be lifted so as to ride over the coarsest of the ore during the early stage of grinding. .the speed is 4 to 18 revolutions per minute. (Richards 1908)

Arrastras were the first industrial process devised to meet a specific mineral processing need. They came into use in Mexico starting in the late 16th century, where they were driven by donkeys. After 60 years of mining, the high-grade ores suitable for direct smelting were exhausted, and this left only ores containing less than 200 oz of silver per ton. These ores were finer grained, the deposits were huge, and the profits to be made were high, so a process was needed to grind these finer silver ores and increase the quantity of silver being sent from Mexico to the Spanish king.

Although a chemical process in which the ore was mixed with water, common salt, copper sulfate, and mercury was not new (it had been described in the first complete textbook written on metallurgy [Biringuccio 1990]), little was known about it in Spain in 1585. At that time, Bartolome de Medina, a wealthy Seville merchant, learned from a German citizen, Maestro Lorenzo, that fine grinding and amalgamation might work. In 1587, de Medina developed the patio process, in which an arrastra ground the ore and promoted a chemical reaction by slow mixing at the same time.

Grind the ore fine. Steep it in strong brine. Add mercury and mix thoroughly.

Repeat mixing daily for several weeks. Every day take a pinch of ore mud and examine the mercury. See? It is bright and glistening. As time passes it should

77

|

|

darken as silver minerals are decomposed by salt and the silver forms an alloy with mercury. Amalgam is pasty. Wash out the spent ore in water. Retort residual amalgam; mercury is driven off and silver remains. (Probert 1969)

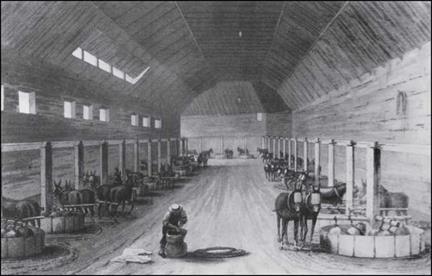

De Medina made the patio process work in a plant in Pachuca, and it came to be used at many mines in Mexico, leading the nation to become the world leader in the production of silver. Figure 6.5 is a lithograph depicting the patio process and arrastras used at the Hacienda de Salgado in the 1820s.

The arrastra was based on the idea of breaking particles by trapping them between a moving weight and a fixed surface, and this idea was used in several machines in the

|

FIGURE 6.5 Arrastras at the Hacienda de Salgado in Mexico in the 1820s (H. G. Ward, Mexico en 1827, London: H. Colburn [1827]; reprinted by permission from University San Luis Potosi) |

1880s. The pit was 0.3-0.6 m deep and 3-6 m in diameter, and 0.3-0.4 tons was a common weight for a stone. Eventually, vertical circular stones with wide rims called tahonas replaced the drag stones in most arrastras, and in this form they became conventional edge mills. Tahonas rotated in circular tracks and could be driven easily by mules. They were typically made of basalt, with a diameter of 1.4-1.8 m and a thickness of 0.6 m, and they rotated on a flat stone, about 2 m in diameter, in a vessel shaped like a cup to prevent spilling of the ore. One or two tahonas were used in each arrastra. In many circuits, the ore was ground to -6 mm in a stamp mill, then to -0.25 mm in an arrastra after which the amalgamation process would start. Figure 6.6 shows a monument representing an arrastra with a tahona that was built to commemorate their importance to the Mexican economy.

A descendant of the arrastra is the vertical roller mill, which is used extensively for dry grinding high volumes of soft, less abrasive materials such as coal and limestone. As better abrasion-resistant materials became available, vertical roller mills were increasingly used to grind cement clinker and mildly abrasive mineral ores.