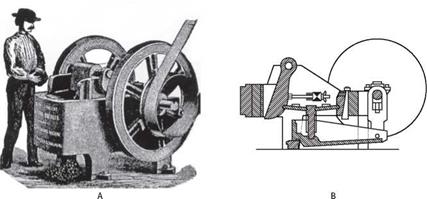

Philetus Gates was one of several inventors who patented rudimentary designs incorporating the idea of a circular crusher between 1860 and 1878, but it was not until 1881 that he patented a successful gyratory crusher (Dickinson 1945). Figure 5.11 shows how the original Gates crusher worked, and early models are shown in Figure 5.12.

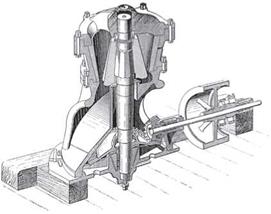

The Gates crusher consisted of a vertical cone suspended at the top and held by an eccentric sleeve at the bottom that gyrated within a fixed cone. Crushing occurred around the periphery as the movable crushing surface, named the mantel, approached to

|

FIGURE 5.10 Blake jaw crusher: (a) general view (b) mechanism (Lebeter 1949b; reprinted by permission from Mining Journal [formerly Mine & Quarry Engineering]) |

|

|

FIGURE 5.11 Gates gyratory crusher (Louis 1894)

and receded from the fixed crushing surface, named the concave. The circular top gave a larger feed opening and reduced blockage. The first sale of a Gates crusher predated the patent by several months when a No. 2 crusher was sold to the Buffalo Cement Company in New York in 1880. That was the first of several thousand gyratory crushers that carried the name of Gates to the far corners of the earth (McGrew 1950).

The Blake and Gates crushers were rival machines, and the custom of the day was to conduct trials between competing pieces of machinery and award the sales contract to the winner. In 1883 in Meriden, Connecticut, a contest was staged between a Blake jaw crusher and a Gates gyratory crusher. Each machine was required to crush 7 m3 of stone, with feed size and discharge settings being similar. The question of productivity was quickly settled when the Gates crusher finished its quota in 20.5 minutes and the Blake crusher in 64.5 minutes. “This must have been a sad disappointment to the proponent of the Blake machine who happened to be the challenger” (McGrew 1950).

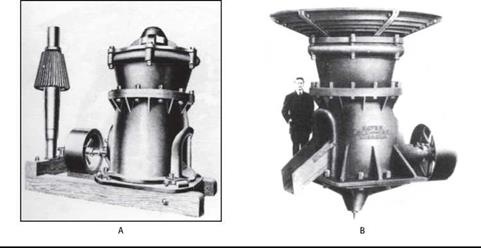

The Blake jaw crusher and the Gates gyratory crusher are still the preferred primary crushers today, and their designs have changed little from the originals. The Gates crusher soon became very popular. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the

|

FIGURE 5.12 Gates crushers: (a) built in 1880 and (b) in 1910 (McGrew 1950; reprinted by permission from Primedia) |

trend was to increase crushing capacity by duplicating small units. “In 1915 at the huge Homestake gold ore mine in South Dakota there were no less than 22 small Gates gyratory crushers to prepare the ore for the batteries of stamps containing a total of about 2500 stamps” (McGrew 1950).

The development of jaw and gyratory crushers had a major impact on large mining operations. In many large open-pit mines, steam shovels were used to fill the ore cars with ore that had been blasted from the face with dynamite, and steam locomotives pulled the loaded cars to the primary crusher. Similar loading and transport systems were used for major civil engineering works, and photos of the Panama Canal show the steam shovels and rock trains used in its construction. The early large open-pit mines such as Utah Copper’s Bingham Canyon mine near Salt Lake City, Utah, and the Hull Russ Iron Ore pit near Hibbing, Minnesota, incorporated steam shovels and railroad transport systems in their original operations. For their driving energy source, the shovels went from steam engines to internal combustion motors and then to electric motors.