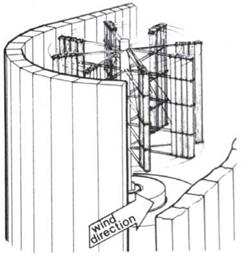

Historically, the wind has also been an important source of renewable energy for driving grinding mills. “Crude vertical-axis panemones have ground grain in the Afghan highlands since the seventh century” (Gipe 1995). Panemones had walls to direct the wind past vertical sails that were attached to a rotating axle, as shown in Figure 4.7.

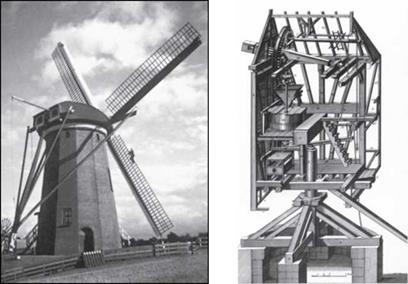

Windmills existed in arid areas of Persia in the 10th century, were used in France by 1180, and came into use in England by 1185. They became a significant source of power in locations where the wind was fairly dependable. Gipe (1995) reports that, by the 19th century, 500,000 windmills were used in China, with an equal number in use in Europe. Wind power was used for general grinding, including: corn and grains; flint for making china, gunpowder, and clinker; chalk for making whiting; and minerals for dyes and paint. It was also used for many other duties such as pumping, sawing, and pressing oils from seeds. Figure 4.8 shows a windmill and the mechanism for driving the querns. Early photographs of the Netherlands feature large windmills being used to pump water from land below sea level back into the sea.

The windmill, as perfected by the British millwrights of the 19th century, was an extraordinarily sensitive and sophisticated machine. The vagaries of the wind, always a fickle and uncertain source of power, made windmills more complicated and less reliable than the water mill and demanded very different skills of the miller.

In the water-powered corn mill it was possible, by adjustment of the hatches, to achieve a more or less uniform speed and thus ensure an even texture in the meal produced. The windmill, however, demanded a different solution. The force of the wind was constantly changing, and this had a curious effect on the action of the stones. As the speed of the mill increased, the runner stone would tend to rise on its spindle, opening the gap between the grinding surfaces and making constant adjustments necessary in a choppy breeze (Reynolds 1970).

Grinding grain in stones driven by the wind must have seemed like a dream come true. The mill rotated to the music of the wind in the sails, and the grinders worked under

|

|

FIGURE 4.7 Panemone—an early windmill (Gipe 1995)

|

FIGURE 4.8 Windmill and the internal mechanism showing the grinding stones (Reynolds 1970) |

conditions far removed from the terrible conditions many had suffered for thousands of years. John Oliver of Sussex was one miller who appreciated the new technology. An excerpt from Corn Milling evoked the idyllic lifestyle that he seemed to enjoy for much of his career:

The vicinity of a mill may have often been desired as a place for burial: but so far as we know there was but one miller who, entertaining such a desire, had it realized—

John Oliver of Highdown Hill, Sussex, who, in 1766, he being then 57 years of age,

|

|

|

prepared his tomb beside his mill on the hill, and erected a summer house beside it, where in quiet hours he sat in meditation. For seven and twenty years he thus alternately tended the mill and the grave, till, in 1793, when he ceased his labours, he was obediently carried from the one to the other. …He left by will 20 pounds a year for the tending of the tomb and the summer house, but of their ultimate fate we have no knowledge. (Bennett and Elton 1898-1904)

Millstones are still used in water-powered flour mills in villages close to reliable water sources and for making stone-ground, whole-grain flours in rehabilitated grinding mills using stones to make the grind.