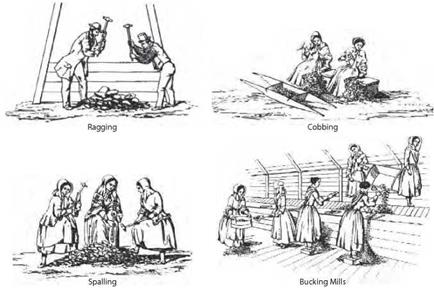

The second stage of size reduction in mining was manual crushing of mined rocks to sizes suitable for direct use or further breakage (see Figure 3.16). Manual crushing was widely used until the end of the 19th century and is still used in many regions of the world. By 1900, the nomenclature for hand crushing was well defined (Foster 1894):

■ Ragging: breaking very big rocks with large sledgehammers weighing 3.5-5.5 kg

■ Spalling: similar to ragging but breaking small rocks with 1.8- to 2.3-kg hammers

■ Cobbing: using a small hammer to knock waste from rocks

■ Bucking: using a broad, flat hammer, about 100 mm square with a flat face, to reduce ore to coarse powder

Men did the ragging, but women and even children were involved in spalling, cobbing, and bucking. The drawings in Figure 3.16 put these exhausting occupations in a much more elegant light than existed in practice. The same may be said of “bal maidens,” the name by which the women who carried out the cobbing in the tin mines of

![]()

|

|

|

Cornwall were known. It may have been a charming name, but there was nothing charming about the work.

Breaking rocks by hand was always a difficult and disliked occupation, but it was necessary in both civil and mining engineering. In England,

…a certain quantity of broken stone was frequently exacted as a task from vagrants in casual wards as a return for food and lodging; the work was, however, so greatly hated that those wards that imposed it were studiously avoided by the fraternity. (Dickinson 1945)

Yet, there were a few who regarded hand breakage in a more kindly light. “The Roadmender,” for example, was a wonderful, if unintentional, tribute to the men who broke stones on the roads (Fairless, circa 1900). The author of this essay eloquently described the observations of a philosophical roadmender who worked alone and took advantage of the silence and loneliness to observe the passing parade as he broke and laid the stones, “…noting the changes that progress brings even in that quiet countryside.” She finished her work with this observation of the roadmender: “I have learnt to understand dimly the truths of three great paradoxes—the blessing of a curse, the voice of silence, the companionship of solitude.” This was a gracious comment about an activity that brought untold misery to countless numbers of people.

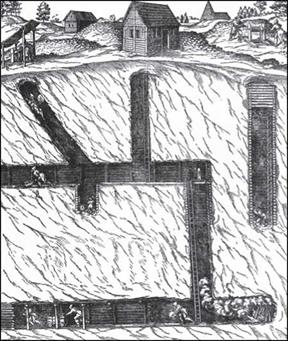

Breaking rock by blasting with explosives started in the 17th century and slowly became part of mining practice. This required that holes be bored to put the explosive inside the rock. Rock drilling was not a new art: “The use of diamonds for rock boring was known to the ancients” (Drinker 1888), and “The ancient Egyptians are said to have used corundum dust or pebbles in order to drill holes in porphyry” (McGregor 1967). The drill holes in ancient times would have had small diameters but holes for explosives had to be larger. Until 1696, holes were 50-62 mm in diameter, 1 m deep, and held 1 kg of powder (Drinker 1888).

It was estimated that with good hammers and bits three men could drill a hole 2-m deep in granite in 5 to 6 hours depending on the rock and the location where the work was done.

In single hand hammer drilling the bit was held and rotated in one hand struck by a 1.8 kg hammer held in the other for drilling 32 mm size hole. For drilling deep holes a double hand drill was essential. One man held the bit, the second man struck it by a 4 kg hammer. (Chugh 1985)

CONCLUSION

Since the dawn of human history, we have needed to efficiently reduce the size of materials to make usable products. The pressures driving this technology’s development—the need for larger, more reliable, and more efficient sources of energy; for larger, more efficient machines; for wear surfaces with longer lives; and for machines and methods that produce finer products—have always been the same. Only the techniques have constantly changed and improved to meet the challenges of all the differing, and sometimes competing, technology requirements.