In early human history, rocks used for buildings, monuments, or metal extraction were mined by hand using hammers, levers, and wedges made from stone, wood, or bone.

|

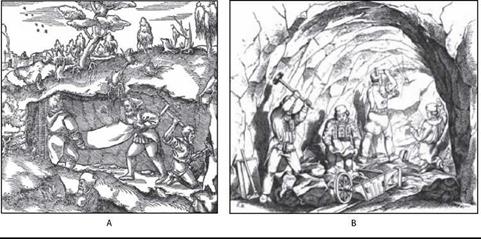

FIGURE 3.14 Hammer and gad mining: (a) 15th-century woodcut (Agricola 1950) (b) 18th — century drawing by Eduard Heuchler showing mining and manual breakage. One exhausted miner is resting (Paul 1970). |

This was the first stage of size reduction, and the procedures used are shown in the woodcut and drawing in Figure 3.14. They varied little from the Stone Age to the 17th century when explosives were first used to break rocks. The hammers and gads used 100 centuries ago are still in use today, albeit with good-quality steels instead of stone. Like the mortar and pestle, they will always be used.

Fire was introduced at least 4,000 years ago to crack the rock and make boulders easier to remove (Drier and Du Temple 1961). Figure 3.15 shows fire setting as it was practiced in 1500 AD. Wood was burned against the rock face for hours until it became very hot. It was then cracked naturally or water was thrown against the rock to induce cracking. Pebbles and boulders could then be easily pried away. The intense heat and toxic fumes made fire setting underground a dreadful task, but it could be controlled and was safer than explosives. It was still used in tunneling and underground mining in Europe and Japan late in the 19th century with advances of 1.5 m to 6 m per month being achieved. Fire setting became legendary with Livy’s story of Hannibal using fire and vinegar to shatter rocks in the Alps to make a track for his elephants (Drinker 1888).