His berries, nuts, acorns and corn were pounded into meal; and his invention of the first pounding appliance constituted, without doubt, one of the earliest attempts to devise an instrument useful in the peaceful arts. (Bennett and Elton 1898-1904)

In this chapter we discuss how stones driven by muscle power—which were first used for grains and later for ores, pigments, and drugs—advanced from the simple mortar and pestle (which produced coarse grains) to the saddlestone (used for much finer grinding) to the complex rotary quern (the first complete “machine”).

MUSCLE POWER FOR BREAD

Since the beginning of humankind, the staple in our diet has been bread made with flour, which is produced by reducing the size of grains. Wheat grains consist of endosperm (~82%), germ (~2.5%), and bran (~15.5%). Flour production involves grinding grains to separate endosperm from bran, removing as much bran as possible, then grinding the endosperm to flour.

Originally grains were softened by soaking in water, and the entire softened grain was baked into bread. Legend has it that soaking led to brewing:

The Egyptians believed that one day Osiris, god of agriculture, made a decoction of barley that had germinated with the sacred waters of the Nile and then, distracted by other urgent business, left it out in the sun and forgot it. When he came back the mixture had fermented. He drank it and thought it so good that he let mankind profit by it. (Toussaint-Samat 1994)

Accidental fermentation may well have been the process preferred by workers during the hot summers, but it did not produce enough soft grain to eat, so the grains were ground with hand stones. Shear and compression forces break the husks away from the endosperm in cereal grains when particles are passed between a rotating surface and a fixed surface. For thousands of years, these forces were harnessed to make flour in family dwellings by grinding grain in small hand-operated mortars and pestles and with saddlestones.

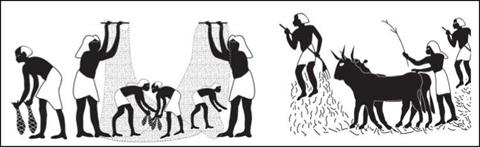

In ancient Egypt the process was to crush the grain lightly in a mortar, separate the liberated bran by winnowing and coarse sieving, regrind the endosperm with a hand stone, and remove more bran by fine sieving with sieves made from hair or fine vines. The same process was also used in the Greek and Roman empires. Simple hand stones are shown in Figure 3.1.

Visitors to the underground cities in Cappadocia, Turkey, can see an example of a 2,000-year-old hand stone—pictured in Figure 3.2—used for grinding spice and foodstuffs. The underground cities were built during the course of hundreds of years by cutting rooms into the soft volcanic tuff. They consisted of tunnels, rooms, and ventilation

27

|

FIGURE 3.2 (a) A 12-ton grinding stone used for grinding spices and other food products in the underground city at Derinkuyu in Cappadocia, Turkey, more than 2,000 years ago. (b) A sketch of a section of the city. The communal grinding stone was on an upper level (adapted from Demir 1998).

|

|

|

FIGURE 3.4 A painting on a tomb in Egypt from about 1400 bc. After oxen break the husks from the kernels, the husks are rejected by winnowing (Casson 1966). |

shafts, which were extended downward through many levels. During times of danger, theses underground cities served as residential quarters for thousands of people. The hand-grinding stone shown in Figure 3.2a was made from ignimbrite, a hard volcanic tuff, and is 2.5 m in diameter, 1 m thick, and 12 tons in weight. Its size made transport through the curved, narrow, sloping, dark passages of the underground cities extremely difficult.

Another type of hand stone used for breakage was the “hopper-rubber,” a rectangular stone with a V cut into it. The V was wide at the top and converged to a narrow slit at the bottom. Nuts and grains were pounded and rubbed until the fragments were small enough to pass through the slit.

The photograph in Figure 3.3 shows one of many stones that were part of the cargo on a boat that sank in the eastern Mediterranean Sea about 300 bc. (The stones were recovered and are on display in a museum in Gyrenia in northern Cyprus.) There was a considerable trade in these stones, which were large, heavy, and resistant to abrasion. Because they were expensive, they were used with care so that they would last for many years. Amphoras, which were storage vessels used to transport liquids, fruits, and grains, were found on the same wreck and are also pictured in Figure 3.3. In commerce, these amphoras were as important as grinding stones.

Other methods were also used for breaking grains. A painting on the wall of a tomb in Egypt dating from about 1400 bc shows oxen treading husks from kernels and the husks being removed by wind currents in a winnowing process (see Figure 3.4). Because bread was the main food for rich and poor alike, it was all important in social and political affairs for more than 5,000 years. Caesar, Antony, and Claudius, for example, wanted Egypt for its grain (Jacobs 1944).

Bread reigned over the ancient world, no food before or after exerted such mastery over men. The Egyptians who invented it based their entire administrative system upon it. The Romans converted bread into a political factor, they ruled by it, conquered the entire world by it and lost the world again through it….

It is hard to imagine that in the 2nd century ad Africa from Tunis to Tangier was one vast Roman field of wheat. The great accomplishment of the Romans consisted not in their introduction of Roman law or Roman police but in their making farmers of hundreds of thousands of nomads. (Jacobs 1944)

Grinding was also used in antiquity to prepare pigments and drugs:

The Ebers papyrus, which was probably written about 1500 bc is the longest, most complete, and most famous of the medical papyri. …About 700 drugs, made up into more than 800formulas, are found in the Ebers papyrus….balances have been found along with mortars, mills and sieves used in preparing drugs. (Magner 1992)