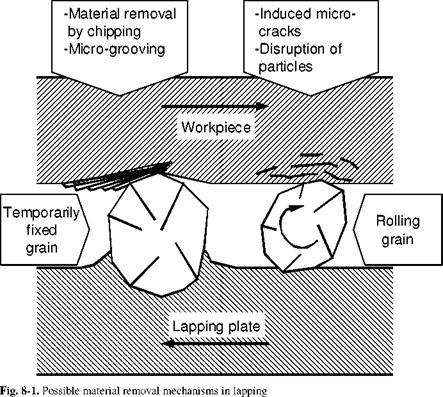

Lapping is a mainly room-bound process with geometrically undefined cutting edges. It is a production and finishing process, respectively, defined as chipping with loose grains distributed in a fluid or paste (lapping slurry) which are guided with a usually shape-transferring counterpart (lapping tool) featuring ideally undirected cutting paths of the individual grains [DIN78a].

The ultra-precision machining method of lapping is followed, according to the desired surface quality, by the polishing process. In polishing, the components are pre-lapped in order to achieve high material removal while maintaining a good surface quality and dimension and form tolerance [KOEN90]. Polishing is then performed in order to create highest surface qualities, including a mirror finish.

Lapped surfaces exhibit, almost exclusively, undirected processing traces, a semi-gloss appearance and, when under strain, are distinguished by little wear.

Surfaces to be lapped are usually flat. If the workpieces have different geometric shapes, correspondingly modified method variations must be applied, in part manually and with auxiliary tools. From an economic perspective, these are not always reasonable choices of application. Given high demands on the quality of the workpiece, however, flat or cylindrical lapping has proved competitive in comparison to ultra-precision turning, precision grinding or honing. Often, it is the only option to achieve the quality requirements needed.

The following materials can be processed by lapping: metals, ceramics, glasses, natural materials like marble, granite, basalt, any kind of gem, plastics, materials used in semiconductor technology, as well as carbon, graphite and even diamond. Geometrically complex components with little form stability can be embedded in a supporting mass (e. g. plastic), thus expanding the area of application of lapping methods.

Lapping distinguishes itself from other machining methods through the following characteristics:

• Most workpieces can be processed without being clamped or fixed.

• Allowances of 0.2 to 0.5 mm (analogue to grinding) are economically machinable today.

• Precision and ultra-precision machining can be executed in one operational step.

• Changeover times are very short.

• Components of less than 0.1 mm thickness can be machined.

• The highest surface and roughness requirements can be met.

• The minimal heating effect prevents undesired thermal distortions and structural changes in the workpiece.

• A consistent machining quality is guaranteed for composite materials.

• Lapped surfaces rarely exhibit tensile distortion or burr formation.

• It is possible to machine multiple workpieces in one operational step.

|

|