Iron or “ferrous” alloys are the most ubiquitous metals in industry today. They include numerous classes of cast iron, carbon steels, tool, alloy and stainless steels, as well as exotic materials for the aerospace, nuclear, and medical industries. In their oldest and simplest forms, iron alloys depend on their carbon content and composition. Cast iron contains carbon in excess of the solubility limit in the austenite phase. It is used mainly to pour sand castings because of its excellent flow properties that make it ideal for complex cast shapes. It is most commonly found in automotive engine manufacture (blocks, manifolds, cranks, small cams). Cast iron is generally very brittle compared to steel and incompatible with most forming operations such as drawing or forging.

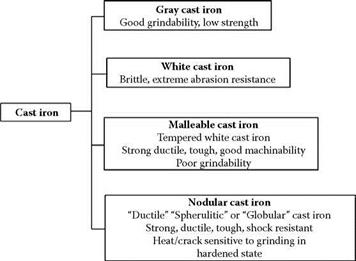

The properties of cast iron (Figure 13.1) depend heavily on how the carbon is distributed.

13.2.1 Gray Cast Iron

Gray cast iron is so called because it gives a gray fracture due to the presence of flake graphite. Its grindability is very good, in either the soft ferritic phase or the harder pearlitic phase, as the graphite disrupts the metal flow to produce very short chips. It is relatively abrasive, especially in the pearlitic phase, requiring either a hard alox wheel grade or preferably the use of CBN.

13.2.2 White Cast Iron

White cast iron is an extremely hard alloy produced by rapid cooling of the casting to combine all the carbon with iron to form cementite. When chipped, the fractured surface appears silvery white. White iron has no ductility and is thus incapable of handling bend or twist loads. It is used for its extreme abrasion resistance as rolls in mills or rock crushers. White iron is very heat sensitive and prone to cracking. It is usually ground with free-cutting silicon carbide abrasive wheels but recently white iron has begun to be ground with vitrified CBN in some applications.

|

FIGURE 13.1 Classes and properties of cast iron. |